Adopting the Building Blocks for Business Process Management

According to IVI’s IT-CMF, the term Business Process Management (BPM) refers to a collection of methods, policies, metrics, roles and technologies to identify, design, monitor, optimize, and assist in the execution of an organisation's activities. It is the combination that enables an organization to be agile in meeting its objectives by efficiently introducing and improving new business processes.In general, there are four key building blocks in constructing an effective BPM practice. The four building blocks are:

- Performance measurement;

- Continuous process improvement methods;

- Business Process Management technologies ; and

- Organisational transformation.

|

| Figure 1: Four Building Blocks of BPM |

In previous article we have talked about the various process improvement methods which I will not repeat. The following sections focus on two of the building blocks as a part of the solution to the challenges identified earlier – organisational transformation and BPM technologies. Also keep in mind that the building blocks are interdependent and not in isolation.

Adapting A Matrix Organisation Structure

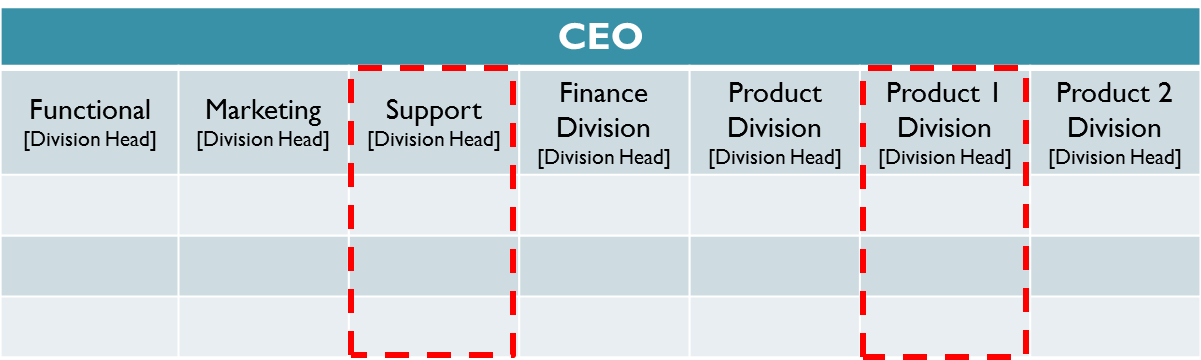

Recall that process improvement method itself is inadequate in achieving improvement of the end-to-end cross functional processes. Hence one of the aspects of organisational transformation is adapting a process centric organisational structure. A useful approach is to adapt a matrix organisational structure as a transition from a functional biased organisation to a process centric organisation. Figure 2 is an illustration of a high level view of a functional organisational structure versus a matrix structure where an executive process owner is identified for each value chain of the organisation but maintaining the function based divisions.

|

|

| Figure 2: Function Based Structure versus Matrix Structure |

The adaption of a matrix organisational structure is the basis for creating accountability for the performance of the large, cross functional enterprise processes. Such accountability ensures deliberated and collaborative efforts among the functional units to manage the end-to-end processes leaving no whitespaces in between them. It will also align the improvement efforts across the functions without jeopardizing the overall performance. Also key to note is the accountability is not just one off during a process improvement project but on-going in day-to-day operation.

Note:

Avoid having a committee to be accountable for the end-to-end process, especially committee made up of the different business units. However, the committee may be a good input to the executive process owner. It is the executive process owner that is accountable for the performance of the end-to-end process, not the committee.

Apart from transforming the organisational structure, there are also other aspects in the organizational transformation including organizational culture that embrace quality, change and innovation.

Scenario: An improvement within a business function (A) was achieved by moving the problem outside that function to a downstream business function (B). Although A managed to improve its performance, B’s performance dropped as it has to cope with a new problem.

A sustainable continuous process improvement is only achievable with the adaption of a process centric or matrix organisation. Just imagine the situation described in the scenario, instead of continuous improvement, the consequence of sweeping problems outside the functional space is a continuous fire fighting patches at the expenses of downstream functions. Although process improvement projects may be able to improve individual processes, it is very difficult to sustain continuous process improvement in the long run.

BPM Technologies

The next building block is the BPM technologies. Again to achieve continuous process improvement, the BPM technologies must be more than simple process design and modelling. It has to embrace the Jidoka or autonomation concept of TPS – a mechanism to enable detect–stop–alert practice in the day-to-day operation. Technology such as Business Process Management System (BPMS) has the capability to monitor and automatically detect problem or enable a worker to raise an alert when problem is identified.A Business Process Management Suite (BPMS) is an integrated suite of software technology that addresses business users' desire to see and manage work as it progresses across organizational functions. A BPMS supports process modeling, design, development, execution via the runtime environment, and monitoring of process performance, in one package or system. Source: Gartner Research

The assignment, management and monitoring of work item in a BPMS is similar to the Andon cord that allows worker to alert supervisor by reassigning problematic work item. The automated monitoring enables on time corrective action to be taken and also initiating process improvement initiative where repetitive problems are identified.

|

| Figure 3: Illustration of Guided Process |

A BPMS can also be implemented to achieve another principle of TPS – ‘fool-proofing’ a process. In such case, the process automation does not remove the worker altogether but enforces a guided process (see Figure 3) that must be followed stringently by the worker with strict quality control in each step. Hence an incomplete or inadequate work item will not be passed downstream creating waste of rework.

In order to meet the fluctuations in demand from the market, a solution based on TPS is to create processes with sufficient flexibility to meet such fluctuations. In TPS workers are to be skilled to handle multiple machines of different types. (see Figure 4)

|

| Figure 4: Workers with Single Task versus Multi Task in TPS |

In other words, in order to meet variations, workers are trained to perform variation of activities or different types of activities depending on the demand. A BPMS is critical in offering such flexibility in process management. The workflow assignment management enables allocation of work items according to the varying allocation methods, availability, competency of workers and demands. Of course, the workers are still required to be skilled accordingly.

Rather than promoting or comparing BPMS to other information technology, this section attempts to introduce the potential solution that a BPMS could bring to close some of the gaps in continuous process improvement and as a key building block of BPM that aligns to the various concepts and practices in TPS and Lean.

Leaving IT applications outside the scope of improvement means the introduction of constraints and limitation to the anticipated improvement. Moreover, changes to legacy IT are not only lengthy in time but very costly. Lengthy in time in the sense that by the time the IT projects are lagging and unable to cope with new changes to the business environments, internally and externally which, require the business operations to make adjustments.

Conclusion

As mentioned earlier the four building blocks are interdependent and not an isolation. Although BPMS could and should (as defined by Gartner) manage work as it progresses across organizational functions, it is more than just putting a BPMS in place. Without the adaption of process centric or matrix organization that emphasizes on executive process owners, the BPMS will end up running functional processes and leaving the white spaces untouched. Similarly, running business process improvement projects without transforming the organisational structure will have limited short term effect within functional units. Without the process management mechanism – BPMS – it is a challenge to roll out fool-proof processes and enabling on-going monitoring and process flexibility.References

- Ohno, Taiichi. 1988. Toyota Production System: Beyond large-scale production. Productivity Press.

- Spanyi, Andrew. 2008. More for Less: The Power of Process Management. MK Press.

- Simons, Robert. 2000. Performance Measurement & Control Systems for Implementing Strategy. Prentice Hall.

No comments:

Post a Comment